Piano tuning

An introduction to equal temperament tuning.

You have been given a (theoretical) keyboard. Inconveniently, this keyboard has not been tuned. You’d like to play it, and therefore decide to tune it yourself. Luckily, the mechanics of tuning this keyboard are easy… you just need to work out which frequency to assign to each note…

The octave doubling rule

You try to recollect any relevant info you might have picked up over the years.. and remember the following:

A note an octave up has double the frequency.

In other words, if note $C5$ has frequency $f$, then note $C6$ will have frequency $2f$. As far as you remember, this should apply to all the notes on the keyboard.

It follows from this that the note an octave below must have half the frequency. So $C4$ would have a frequency of $f/2$.

Great! But where to go from here?..

The first frequency

You allow your eyes to wander up and down the $88$ key (theoretical) keyboard…

You realise that you could pick a relatively middling key, and assign to this a relatively middling frequency.

You choose $A4$ to be your middling key. You then play around with a tone generator, and decide that you perceive $\sim 440Hz$ to be a fairly middling frequency.

You turn on your keyboard, and program in $freq(A4) = 440Hz$.

Great! You have now tuned one note!

All the As

Now that you have decided on a frequency for $A4$, you realise that you can work out the frequencies of all the other $A$s, using the octave doubling rule:

$A4 \leftarrow 440 Hz$

$A5 \leftarrow 2*440 Hz$

$A6 \leftarrow 4*440 Hz$

And:

$A3 \leftarrow 440/2 Hz$

$A2 \leftarrow 440/4 Hz$

And so on.

Great! Now you have tuned all of your $A$s!

Join the dots

You have all the $A$s tuned, but you’re not sure what to do about the other notes.

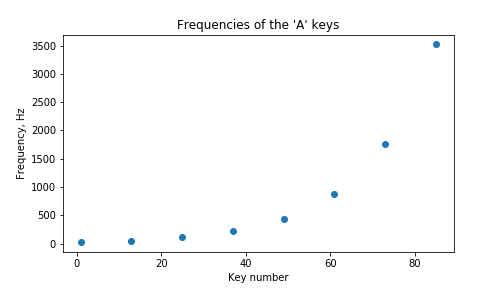

You wonder if a graph might help, so you painstakingly draw out the following:

Looking at this graph, you realise that drawing a curve through the points would assign a frequency to each key on the keyboard. However, drawing a curve looks somewhat difficult..

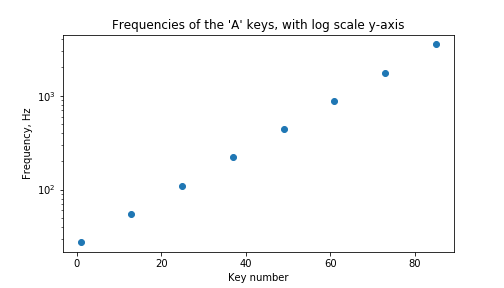

On a whim, you decide to plot the points again, but this time using logarithmic graph paper:

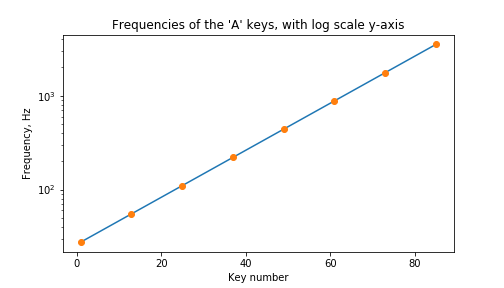

Aha! Now you can use a ruler to draw a straight line through the points:

If you want to find the frequency of a certain key, you can read it off the graph!

You wonder if the octave doubling rule still applies to any note, or just to the $A$s. You read a few values from the graph, and it seems like it does apply to all notes! “Hurrah!” you shout.

Great! By reading from the graph, you can now tune all the notes on your piano!

Finding the expression

Unfortunately, you don’t enjoy reading values from the graph… it’s slow and imprecise.

“If only I had a mathematical expression for this curve”, you think to yourself, “then I could accurately compute the frequencies for this keyboard!”…

You write out the frequencies of the $A$ keys on your keyboard:

| $A$ key number ($n_a$) | frequency ($freq$) in $Hz$ |

|---|---|

| 1 | 55 |

| 2 | 110 |

| 3 | 220 |

| 4 | 440 |

| 5 | 880 |

| 6 | 1760 |

| 7 | 3520 |

After some time spent looking at the sequence, you notice that $880$ is $ 440 * 2^1 $, that $1760$ is $440 * 2^2$, that $3520$ is $440 * 2^3$, and so on. You realise that you can write an expression for frequency in terms of $n_a$:

\[freq = 440 * 2^{n_a-4}\]You put this into a table:

| $A$ key number ($n_a$) | frequency ($freq$) in $Hz$ | expression |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | $440 * 2^{-3}$ |

| 2 | 110 | $440 * 2^{-2}$ |

| 3 | 220 | $440 * 2^{-1}$ |

| 4 | 440 | $440 * 2^0$ |

| 5 | 880 | $440 * 2^1$ |

| 6 | 1760 | $440 * 2^2$ |

| 7 | 3520 | $440 * 2^3$ |

You now have an expression for the $A$s, but what about the keys in between the $A$s? You wonder if you can modify the numbering $n_a$, to allow for other keys… recalling that $A4$ is normally labelled as key $49$ on the keyboard, $A5$ is $61$, etc.. You write a table, showing how $n_a$ maps to the standard key number $n$:

| $A$ key number ($n_a$) | standard key number ($n$) |

| 1 | 13 |

| 2 | 25 |

| 3 | 37 |

| 4 | 49 |

| 5 | 61 |

| 6 | 73 |

| 7 | 85 |

You see that you can express $n$ in terms of $n_a$:

\[n = n_a*12 + 1\]You then re-arrange for $n_a$:

\[n_a = (n - 1) / 12\]You realise you can sub this into your expression for freq:

\[freq = 440 * 2^{n_a-4}\]Using this expression, you compute the frequency for all $88$ keys on your keyboard accurately and conveniently.

You celebrate because you have successfully tuned your keyboard.

Summary

You started with the octave doubling rule.

You then selected a key on the keyboard, and assigned it a frequency (a middling frequency for middling key).

This allowed you to fit a curve which gave a sensible tuning for the whole keyboard.

You then found a mathematical expression for this curve.

The tuning system you created is called twelve-tone equal temperament [1]. It is “the most common tuning system since the 18th century”, but not the only tuning system available [2].

The tuning of real acoustic pianos is generally based on twelve-tone equal temperament, but it deviates from this theoritical tuning. To find out more, read up on the Railsback curve [3].

Preserved frequency ratios

A property of twelve-tone equal temperament is that a major third sounds like a major third wherever it is played on the piano. A fifth sounds like a fifth wherever it is played on the piano. A fourth sounds like a fourth wherever it is played on the piano.. As you move a given interval up and down, the pitch changes, but the interval always sounds like that interval. Tuning systems that are not equal temperament do not have this property; a third might sound sharp at some places on the keyboard, and flat in other places. Let’s look at why equal temperament has this property.

Pick key $n$ on the keyboard.

Now pick a key that is $k$ semitones above $n$. This is key $n+k$.

We can write the frequency ratio for the two notes as:

\[r = \frac{freq(n+k)}{freq(n)}\]Let’s plug in our expression for $freq(n)$ from above:

\[r = \frac{440 * 2^{(n+k-49)/12}}{440 * 2^{(n - 49)/12}}\]And simplify:

\[r = \frac{2^{(n+k-49)/12}}{2^{(n - 49)/12}}\]The $n$s have cancelled out! The ratio of frequencies, $r$, only depends on the number of semitones between the two notes, $k$. This explains why in equal temperament, any interval (e.g. a third), has the same character even as you move it up and down the keyboard: the $n$ may change, but the $k$ stays the same, and hence the ratio of frequencies stays the same.

Other tuning systems, such as just intonation [5], lack this property, meaning that a given interval can sound more like the interval, or less like the interval, as you move it up and down the keyboard, because the frequency ratio doesn’t stay constant. For certain notes and intervals these tuning systems may sound ‘better’ than equal temperament, but then for other notes and intervals the sound may be ‘worse’.

References

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal_temperament

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_tuning#Systems_for_the_twelve-note_chromatic_scale

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_acoustics#The_Railsback_curve

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies